His erotic needlepoint paintings show a world where the sexual and the sacred exist side by side: Hell is a hot night club, and Satan is its magnetic daddy.

— Garth Greenwell, 6/21/21

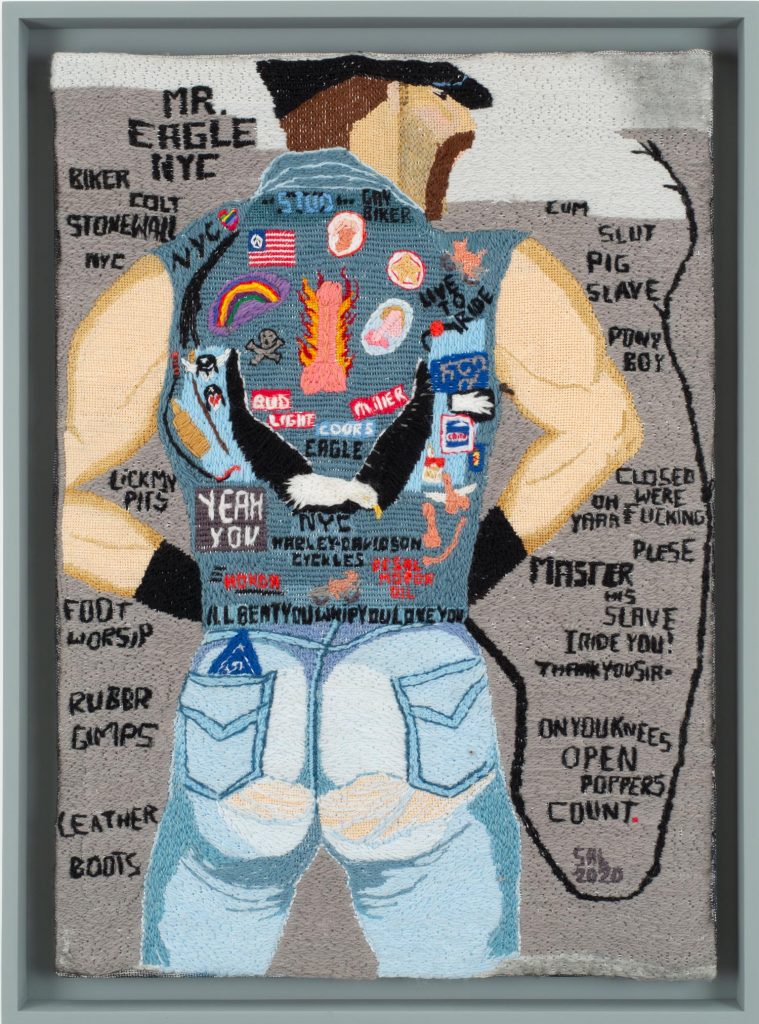

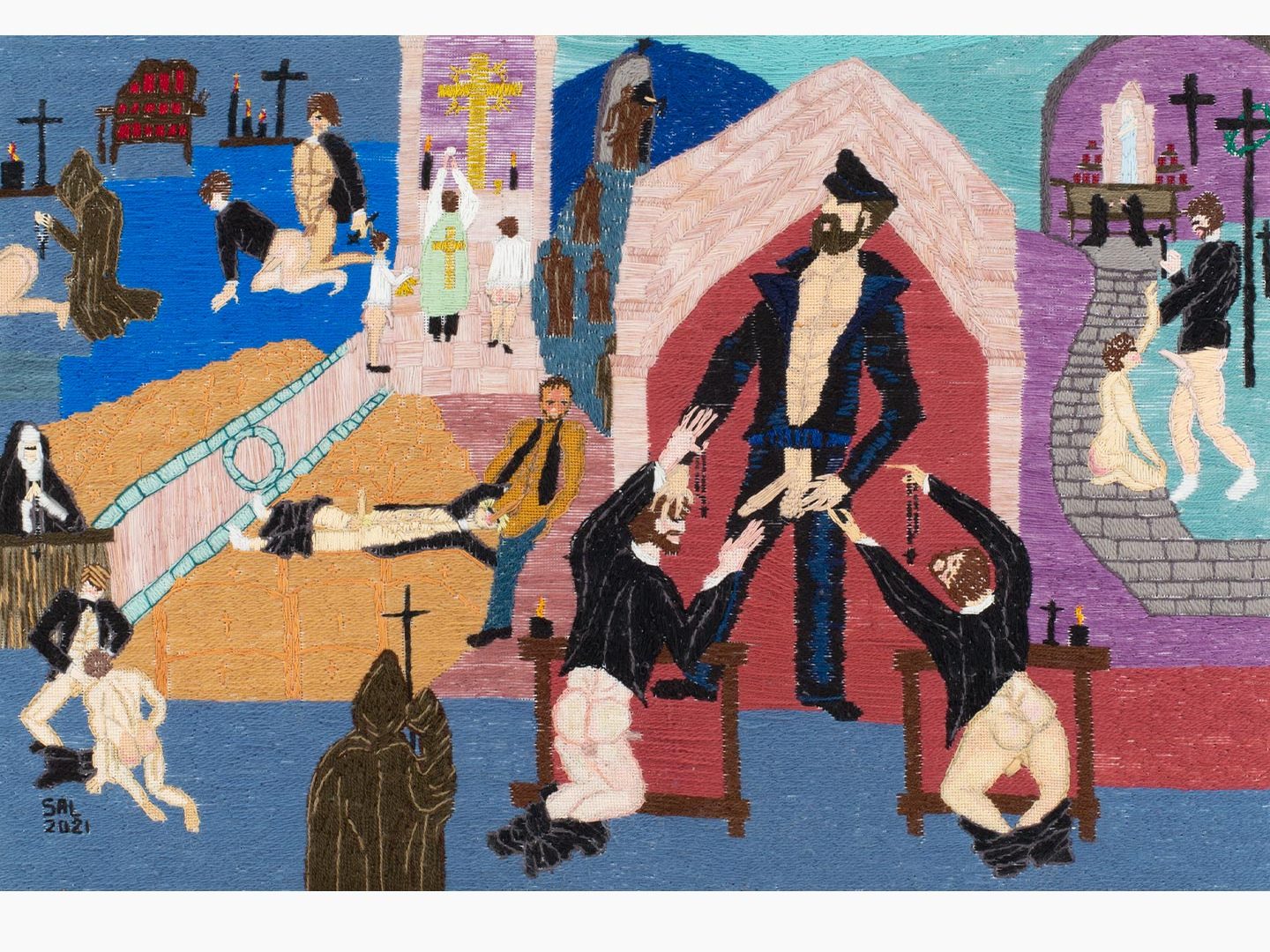

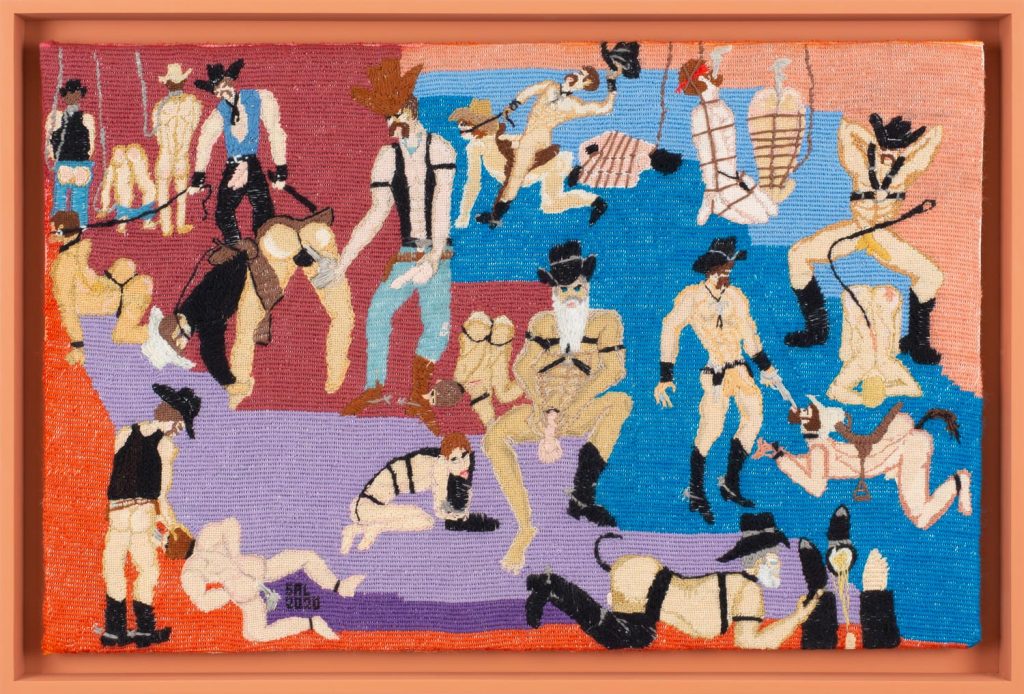

The 75-year-old retired hairdresser Sal Salandra makes large-scale, embroidered canvases—he calls them “thread paintings”—that are intricate, ambitious, subtly crafted, and inventively, incandescently filthy. Men fuck each other in every possible configuration; gagged and mummified men hang from cords; men bind each other with chains, they whip each other; disembodied hands flick cigar ash into drooling mouths. The accoutrements of a certain kind of gay male libidinal exuberance—bottles of poppers, Crisco cans—populate his scenes, as do icons of the gay sexual imagination: the leather daddy, the cowboy; characters from comic books: Superman, Batman, and Robin. And also, most provocatively and powerfully, figures from the Catholicism in which Salandra was raised: orgiastic priests and altar boys, devils and angels, Satan and the crucified Christ.

A consummate outsider artist invigorating a traditional medium with decidedly nontraditional subject matter, Salandra is entirely self-taught, without any formal training in art. Yet he’s quickly gaining acclaim: Inclusion in the January 2020 Outsider Art Fair in New York, just before the Covid lockdown, brought new attention to his work, and the past months have seen his paintings exhibited (sometimes in person, sometimes online) by the Folsom Street Fair, France’s Villa Noailles Hyères, the Tom of Finland Foundation, and galleries in New York, East Hampton, and Nashville. And through July 26, his work is on display in New York at Club Rhubarb, the experimental gallery that artist Tony Cox created in his Chinatown apartment.

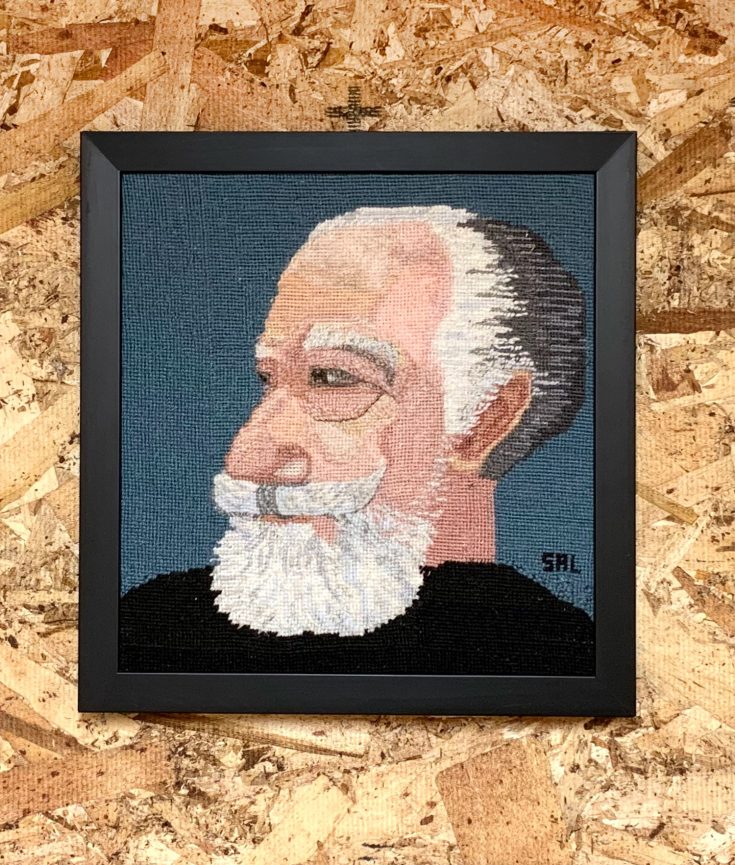

I became aware of Salandra early in the pandemic, and his Instagram page quickly became one of my few reliable joys in lockdown. Earlier this month, he spoke with me about his life and work via FaceTime from outside his home in East Hampton, where he lives with his husband of 43 years. Salandra is handsome and energetic, and looks much younger than his age, with a full beard and handlebar mustache that frequently lifts with his smile. In photos on his Instagram page he often sports a leather jacket, but when we spoke he was in a T-shirt and jeans, a crucifix hanging from a thick chain at his neck. He began sewing in 1980, he told me, when a relative gave him a six-inch needlepoint set while he was bed-ridden with the flu. His subject matter was conventional at first—birds and flowers, elements that sometimes appear in his more transgressive work—but Salandra, who is dyslexic, found following patterns difficult and soon began working from his own designs. After Salandra sold a few of these works, a storeowner put in a request for erotic paintings; Salandra painted his first about a decade ago. The figuration in his early erotic paintings is gestural, a far cry from the intricacy of his more recent work. “The bodies didn’t really look so perfect,” he told me of those early paintings, “because I never took art. But people had the idea. And people started loving seeing these bodies. They knew what was going on.”

Salandra showed me several of his paintings in various stages of completion. He begins with a rough pencil sketch on paper, which he then transfers to a grid canvas. These preliminary plans are never strict, and Salandra often abandons them; once he begins sewing his process becomes improvisatory, he told me, a matter of “dragging lines here and there.” He works from pornographic photographs he saves on his iPad, using them as studies for the male forms he depicts. Sewing fourteen hours a day, a painting will take him more than two weeks. Through all of it, he says, he talks to God. “Now, I told you I’m a little nuts here and there,” he said to me. “I ask God, ‘How do you think a bottle of poppers will do here?’ and ‘Okay, do the poppers work?’ ” He assured me that God answers. “It’s not like you hear God say, ‘Oh, put that bottle of poppers in.’ But you know that God is saying it.”

There’s more than a little of the mystic in Sal Salandra. The son of Italian immigrants, he grew up in Edgewood, New Jersey, part of a large and loving working-class family. “It was so fucking poor and happy,” he told me. He aspired to the priesthood until he was defeated by Latin—because of his dyslexia, Salandra was often dismissed as “stupid” as a child—and was so devout that from the age of 13 to 19 he didn’t masturbate. Once, alarmed after having a wet dream, he went to his priest and asked to enter the confessional to be absolved. “No, no, my son,” Salandra remembers this priest saying, “you kneel here in front of me and tell me what your sin was.” As Salandra recounted his dream, he realized that the priest’s interest was less sacramental than salacious—that he was going to use the details for his own jerk-off fantasies. This was an important moment in Salandra’s disillusionment, part of a journey that would lead him to reject not only Catholicism but all organized religion as, fundamentally, a mechanism of control. This hasn’t severed what he feels as a profound and personal relationship with God—nor has it divorced him entirely from the mysteries of the church. “I believe in God,” he told me, “and I believe that God was whipped and crucified and everything, so he understands the idea of men being tied up and men being whipped.”

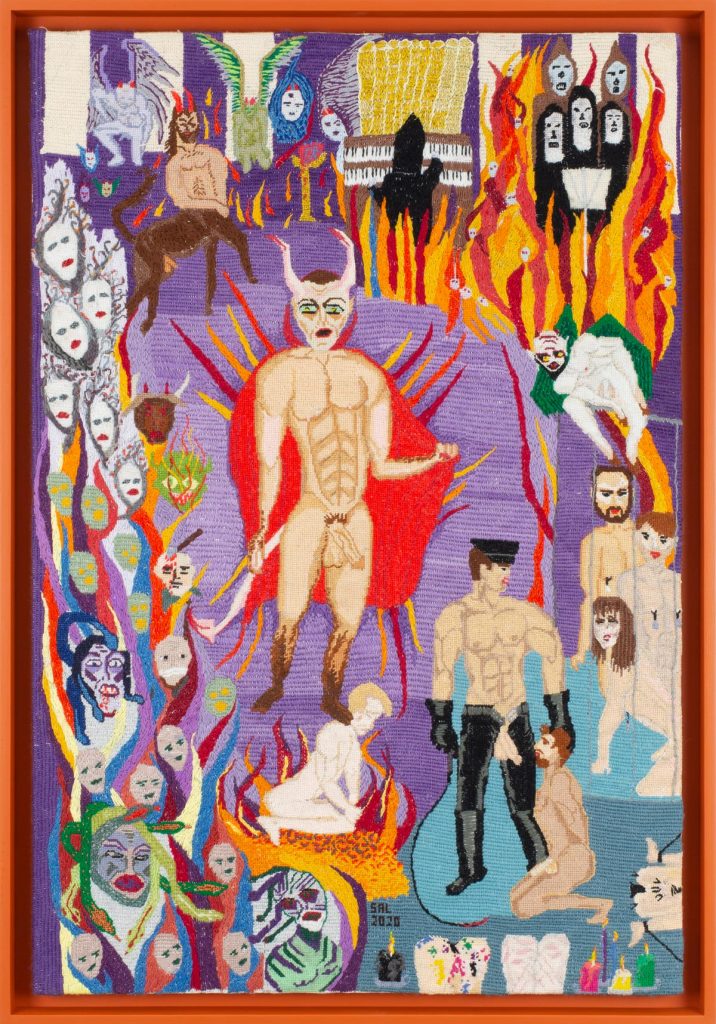

Religion is the theme of his most impressive paintings. In “Mass at Church,” five male couples engage in sadomasochistic games around the central figure of Christ crucified—not nailed but bound to the cross, his posture less agonized than seductive. The altar below him holds candles and crosses, but also dildos; a paddle and cat o’ nine tails dangle beside rosary beads. One man hangs bound and gagged, weights pulling at his nipples and his balls; his placement on the canvas suggests an equivalence with the Christ figure, as if their martyrdoms, too, are given equal significance, each its own path to salvation. In fact there is a curious, interesting flatness to this picture: each of the figures demands our attention, Christ no more than the rest; hanging from a cross seems just another kinky game. The central figure of Salandra’s masterpiece, “Teachings of the Devil,” is a ripped and mascaraed Satan, both regal and comic in his horns and cloak (or are those wings?), with a modest, trimmed patch of pubic hair above the veined pendulum of his penis. His foot rests on the neck of a single, naked, very pale figure kneeling before him in flames.

The marvel of the painting lies in what surrounds this central image, a richly peopled phantasmagoria of diabolical queerness. Flames writhe around the ghostly faces that ascend the left-hand side of the canvas, overseen by drag queen medusas. Winged devils hover over a centaur in the top left, and the top center supplies what to me is the touch of glory: a robed and hooded figure playing an organ, its two keyboards beautifully drawn, golden pipes rising grandly above. Just to the right of this, still encased in flames—in which diminutive figures suffer minuscule torments—a chorus of five ghouls crowds around a music stand, singing with choirboy composure. It’s all virtuosic, hilarious, harrowing—Salandra’s devil paintings manage, in a way I can’t quite understand, to be pure camp and utterly earnest, sometimes devastating expressions of desire. In the bottom right corner a leather daddy holds a whip, his free hand resting on the head of a man kneeling at his feet. Maybe not resting—maybe restraining, since the kneeling man’s body seems tense with desire, as though desperate to lunge for the cock that hangs just inches from his mouth. As in one of Bosch’s terrifying paintings of hell, every inch of the canvas is filled with invention and verve, every inch is psychologically pregnant.

Juxtapositions of Christianity and sex in gay male art are usually mined for pathos, setting up excavations of guilt and shame. Salandra’s paintings are remarkable for how entirely free they are of this dynamic, how full they seem, instead, of joy. In portraying sadomasochistic sex, even in portraying the pains of Hell, Salandra conveys the pleasures of torment, the playfulness in what are often treated as somber, humorless activities. His Hell is a hot nightclub, Satan its magnetic Daddy. The passions that fuel religious and sexual feeling aren’t contrasted in his pictures, which instead give a sense of continuity between the sexual and the sacred. This owes something to Salandra’s experiences as a newly out gay man in New York City in the 1970s, when his twin brother, also gay, introduced him to the world of gay New York’s clubs and bathhouses. “This is what life is about,” Salandra remembers thinking.

The parallels between the rituals of Catholicism and the rituals of certain kinds of gay male sex seemed clear to him: “There’s the cross in the Church, and there’s the dildo in the bathhouse. There’s Christ being whipped and tied up on the Cross, and there’s men being tied and whipped and beaten. All these parallels: the Host, the wonderful Host that we all went to go receive, and there’s the dick, which is the Host to me. So all these things have parallels and the Church was telling me how wrong they were, but they weren’t wrong. Because poppers brought you into this realm with God, which was a dick or an ass or something like that.” Also absent from Salandra’s paintings is any explicit reference to AIDS, which would destroy much of the world that inspires many of his paintings. Salandra’s twin, Anthony, was infected early in the crisis; as a result, Salandra took precautions not to get infected himself. The subject of an article on long-term survivors in The Advocate in 2001, Anthony died of heart disease at 60 in Brazil, where he had gone to be with a lover.

One of the exciting things about Salanda’s Instagram page is to see him making discoveries, feeling his way toward new means of rendering reality in thread. An extraordinary image he posted this April, a detail from “For His Pleasure,” portrays the faded crotch of a man’s jeans, the texture of the denim covering his bulge captured with luxurious realism, like folds of fabric in an El Greco. (“I say, Do you think this is gonna work, God? And I do this and I do that,” Salandra told me of the process of discovering this effect.) Salandra takes inspiration from nature, from pornography, from life itself, he says. “I look at art constantly. But what’s the best art? This,” he said, gesturing at the trees that surround his home, “these trees, these flowers, everything around you is telling you something about art.” He’s constantly gathering impressions and images that he will work into his art. “Your mind is a computer, it’ll throw it back to you when you need it again.”

When I ask him about the influence of other artists, he told me that canons and traditions don’t mean much to him. “To be very honest,” he said, “I look at a painting and it can be from a five year old. And that’s important to me. Or I could look at Matisse and see the way he does it. And that’s important to me. I never remember who their names are, who they are. I just know that I want to be able to paint like that.” Yet the influence of canonical painters seems ever-present as I look at Salandra’s paintings: Bosch in his images of Hell, Michelangelo in the shading of a back. His densely packed, sometimes surreal orgiastic scenes put me in mind of Keith Haring’s “Once Upon a Time,” in Manhattan’s LGBT Center; the striking fields of color that often make up the backgrounds of his paintings are reminiscent of David Hockney or Patrick Angus.

Salandra’s emotions lie close to the skin, and his conversation is shaped by enthusiastic digressions and exhortations. He frequently came close to tears while we spoke, remembering his brother Anthony, or wondering at the warm attention his work is receiving. But the strongest emotion came as he talked about artmaking itself, the long, obsessive hours of work he puts into an endeavor he came to relatively late in life. “I’m sorry,” he said, lifting his glasses to wipe away tears while discussing a new painting. “I just get so excited with it. It’s like, I’m 75, am I going to be able to do enough more of them? Because I just love doing art. I love it. I had no idea.”