September, 2021

Online version of article on ArtForum.com

Sal Salandra didn’t set out to make a body of work stitching together the mundane, the profane, and the sacred. A long career dressing hair in New Jersey had instilled strength and precision in his fingers, but the countless hours standing in a penitent posture as he tended to clients almost broke his back. When it finally gave out, Salandra recuperated in bed. A needlepoint kit, a gift from his mother-in-law, kept his hands busy. The craft must have tied together other strands in his life, for in the coming years, as he honed his chops on floral patterns and commissions for portraits of pets, he came out of the closet, found love, and made a home for himself in the BDSM community. All of these changes penetrated what he began to call his “thread paintings,” the artist’s explicit and fabulous tableaux.

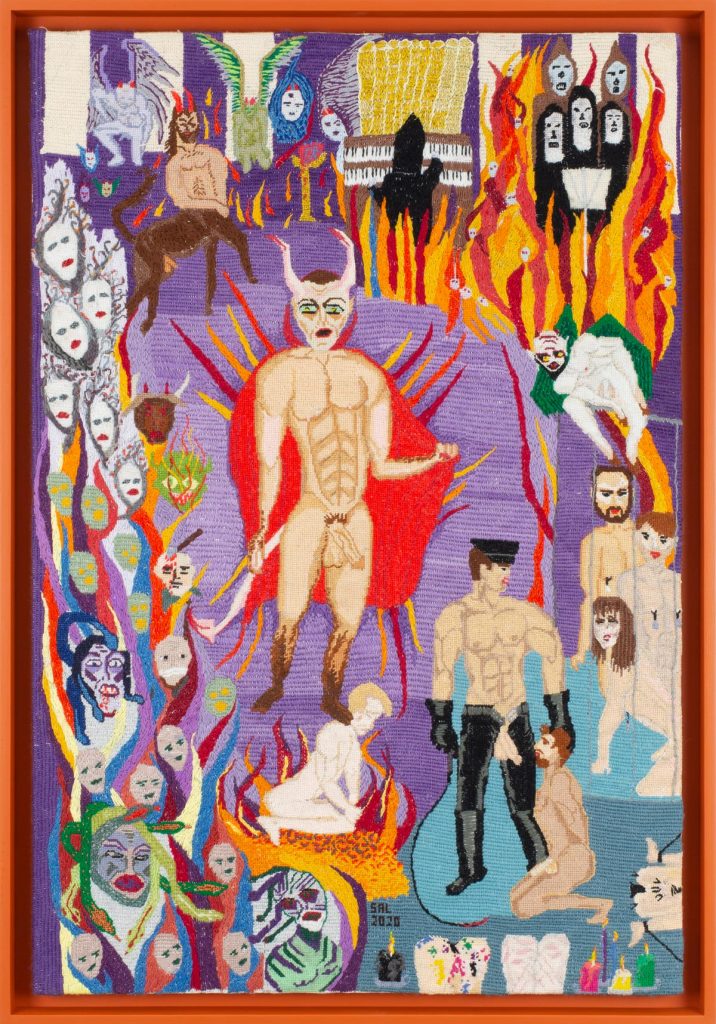

Now seventy-five, the self-taught Salandra installed fourteen works in artist Tony Cox’s apartment-cum-gallery in downtown Manhattan, Club Rhubarb. Part heavenly thrift shop, part infernal erection of the stations of the cross, Salandra’s embroidered images offer liberatory scenes of sexual adventures. Within their candy-colored frames, his crowds of sundry hunks give and take pain without romanticizing martyrdom or retreating into irony.

Salandra, of course, isn’t the first to push needlepoint into adventurous adult terrain—in the mid-1970s, Nicolas Moufarrege, for one, fashioned ecstatic reveries of beefcake and pop culture in his needlepoint-and-paint canvases, while Elaine Reichek and others have explored feminist responses to “feminine” handicrafts for more than fifty years—but his work is uncommonly accomplished and beguiling. He has an eye for the pressure of skin stretched against bone and the skills to replicate it. His figures seem to inhabit their haphazard arrangements as naturally as Howard Finster’s holy folks do theirs, though their physiques and appetites are more those of Tom of Finland than those of Saint Thomas Aquinas.

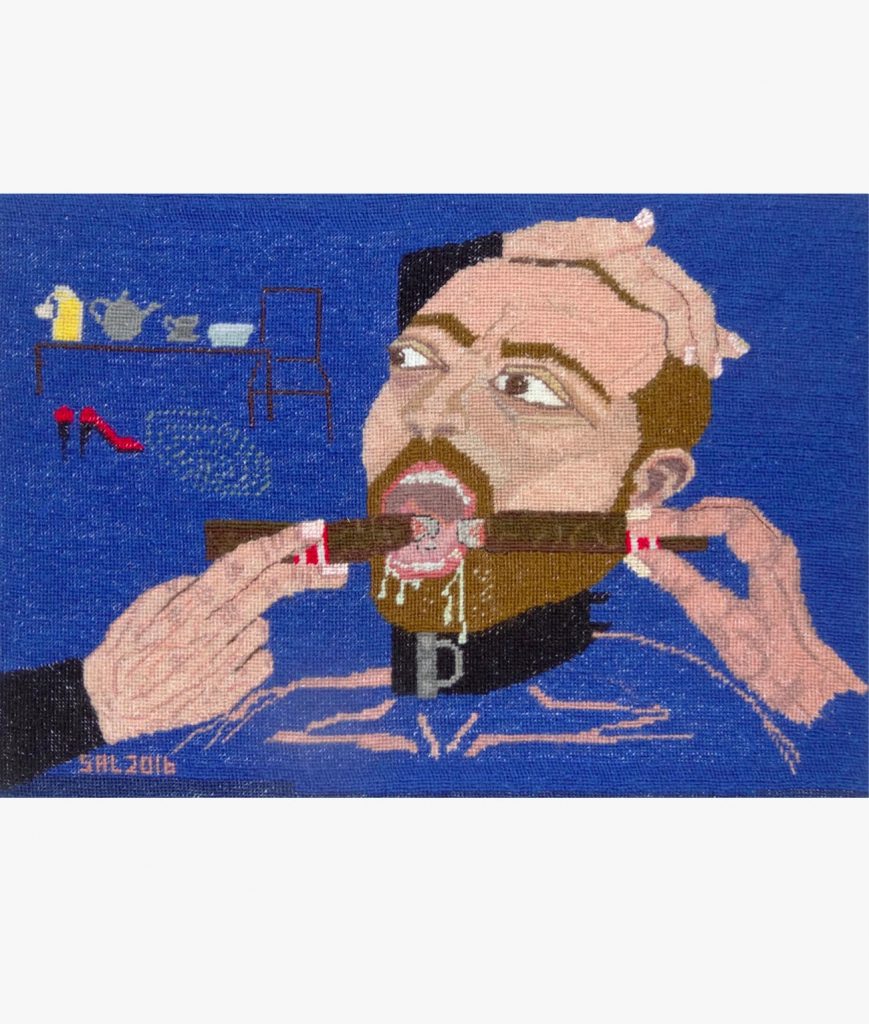

Human Ashtray, 2016, feels like an illuminated manuscript: Two delicately rendered hands work lit cigars across the lips and mouth of the titular subject, whose drool simulates musical notes that dance across his leather choker; a third hand keeps his head in place. His eyes, slightly bugged and pooling with perhaps ambivalent consent, gaze at a distant domestic composition of a pair of red high heels, a teapot, and something like a spiderweb. Or is it the Milky Way? A pool of cum? The background is as blue as a baptismal ocean, as nubby as a childhood blanket.

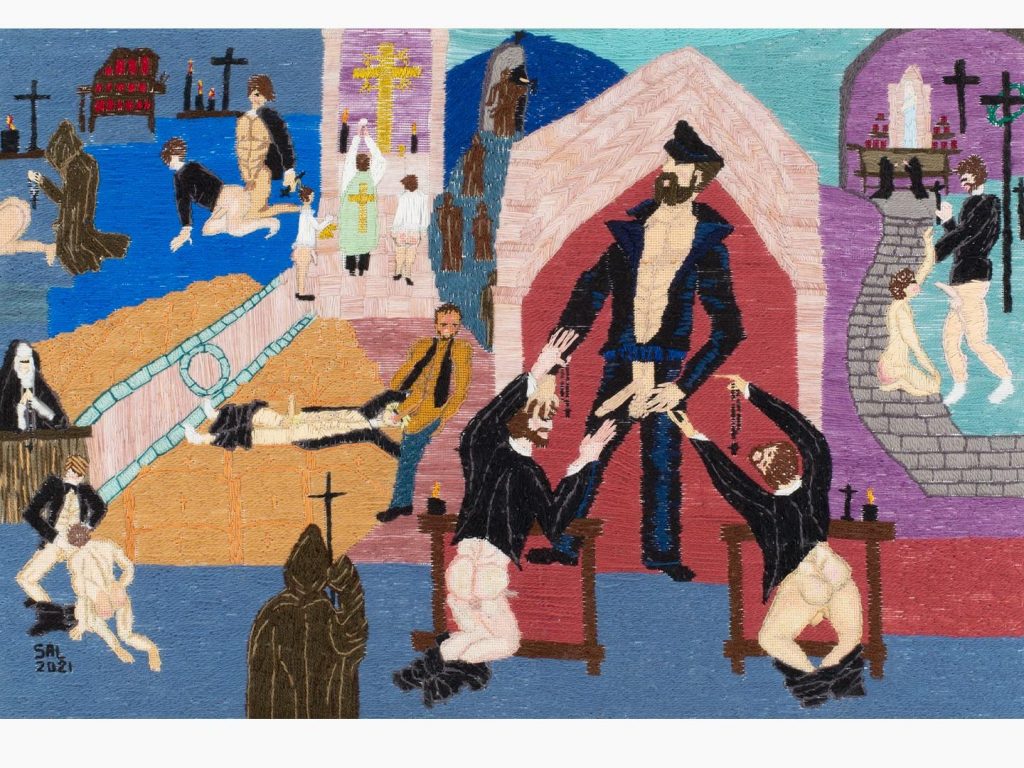

Salandra sinks further into formal complication (and abject filth) with ease. The men of Bad Angels, 2020, play with one another’s assholes instead of on harps as they cruise the rolling white clouds of their heaven, while Jesus and Mary ascend, their feet peeking from beneath their robes, ready for a good shrimping. Lucifer himself instructs a leather daddy on how he should be worshipped in Teachings of the Devil, 2020, as other damned souls, jostling for their place in line, are egged on by gaggles of ghouls having what looks to be, ahem, one hell of a party. In Church Taught Sex Is a Sin, 2021, a pair of priests beg to service a dom at a rickety altar; the ecclesiastical cosplay feels far more infernal than el diablo’s demimonde—though we all know blasphemy is the sweetest form of ecstasy.

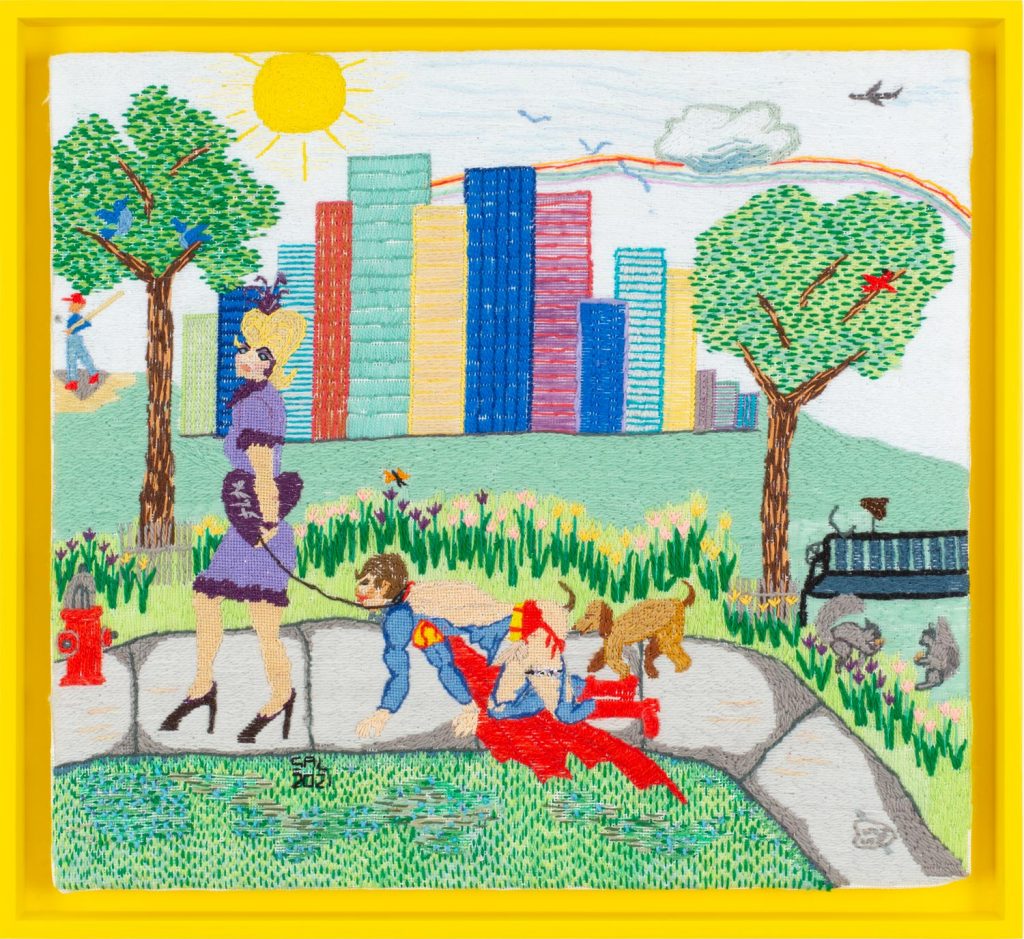

Cox made a wise choice to hang the work in a processional arrangement around the space: the blockbuster Boschian imagery to the north, and various scenarios of those comic-book characters who are without a doubt America’s true gods and goddesses to the south. Sunday Walk in the Park, 2021, depicts a woman taking a jockstrapped Superman, on all fours and tied to a leash, out for an afternoon stroll. The setup is a delightful bit of power play, but the real hero of this picture is the dog prancing behind, nose joyfully up the Man of Steel’s ass. The canine is rendered with such familiar tenderness that I was tempted to believe it might have long ago waddled into the beauty shop on the arm of a Long Island suburbanite in a kind of divine intervention.